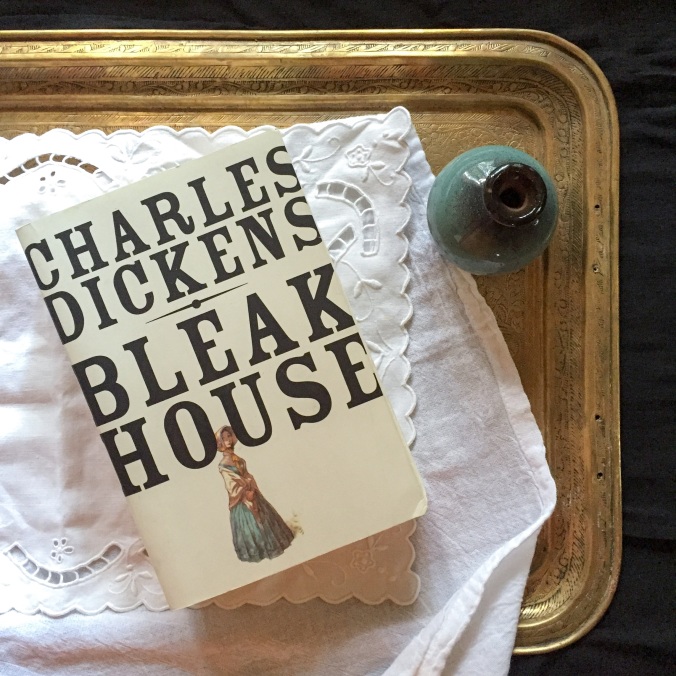

“LONDON. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill.”

Thus starts the novel of epic proportions named ‘Bleak House’.

The opening paragraph of Bleak House grabbed my attention from the very onset of reading the book. It is truly memorable.

G. K. Chesterton wrote of the introduction of Bleak House that

‘Dickens’s openings are almost always good; but the opening of Bleak House is good in a quite new and striking sense’.

Notice how fragmented the sentences are.

The opening is in fact a one word sentence. The fragmented dialogue, in my opinion, give a sense of frenetic activity. Combined with the present tense that it is written in, there is a sense of unrest, tension and suspense- one feels anything could happen at any time.

And the dull, smokey, dusty, foggy picture of London thus presented, serves almost as a metaphor for the state of Victorian society – in dire need of social reform.

It is the perfect way to introduce the reader to the frustration the author feels regarding the cumbersome judicial system which is one of the themes at the heart of this great novel.

‘Bleak House’ is the story of a legal case called ‘Jarndyce and Jarndyce’ which has gone down in the annals of history, for being one of the most long-standing legal battles in British judicial history. Several people’s financial fates are entangled in the trappings of the legal battle. Of them, we are introduced to Mr. John Jarndyce, owner of Bleak House and his wards, Richard and Ada. There are other beneficiaries but despite the different age, social backgrounds and diversity of the persons involved, they all share one thing in common: the feeling that their lives are in a permanent state of unrest. There is a lack of settlement and finality. There is a hope that an outcome will soon be reached in the case and an expectation that life will vastly improve when that occurs. But in the meantime life is exceedingly hard to bear. There is bitterness and resentment.

When middle aged John Jarndyce, offers his wards Richard and Ada a home under his own roof, he extends the same gesture to young Esther Summerson, a young orphaned girl, who knows nothing about her parents, her past or the reason that she should be so favoured by Mr John Jarndyce. Esther’s personal history is a mystery but it is known to her, that the circumstances of her birth are tinged with shame. Esther is brought to Bleak House as Ada’s companion and is soon entrusted with the housekeeping duties of Bleak House. She has a sweet, kind temperament and it is through her eyes that we are told part of the story.

Bleak House is considered by many to be Dickens’ masterpiece. For one, the narrative technique is extraordinary. In Bleak House we observe Dickens using two different types of narrative.

The first is the omniscient narrator who is impersonally telling the story in the third person. The second is the first person narrative via the character of Esther.

Whilst reading the story I immediately felt I was drawn intimately into the story in the ‘Esther chapters’. The tone of the young girl is fresh and innocent although meek and considerably self-deprecating. This contrasts sharply with the satirical rather jaded tone of the omniscient narrator.

In providing this vivid contrast in narrative and the tense in which the story is told (present tense for the omniscient narrator, past tense for Esther) we are alternately pulled in and out of the narrative.

The use of the omniscient narrator broadens the scope of the novel, however. There are certain situations that Esther cannot be part of although we do see the narratives intersecting in certain parts of the novel.

There is another story running in parallel to the ongoings at Bleak House and introduced to the reader by the omniscient narrator. This is the story of Lady Dedlock, an aristocratic, middle aged lady and wife of Sir. Leicester Dedlock, Baronet. We learn that she is sad, exceedingly bored with life, excessively privileged but she has a secret to hide and that secret is known to the family lawyer, Mr Tulkinghorn.

There are other remarkable characters: the ‘childlike’ Mr Skimpole, the mercenary Mr. Smallweed, down on his luck George Rouncewell, conniving Mr Tulkinghorn, annoying Mr Guppy , charitable but short-sighted Mrs Jellyby and more. What amazed me was how Dickens was able to bring all the loose threads of these seemingly unrelated narratives and weave a cohesive tapestry of a cogent story.

It is impossible to do a book of Bleak Houses’s stature true justice through a book review. Nevertheless, I will strive to list some of the reasons why this book mattered so much to me.

1. Spontaneous combustion  (need I say more?).

(need I say more?).

2. A detailed historical glimpse of Victorian London.

“Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snow-flakes — gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun. Dogs, undistinguishable in mire. Horses, scarcely better; splashed to their very blinkers. Foot passengers, jostling one another’s umbrellas in a general infection of ill-temper, and losing their foot-hold at street-corners, where tens of thousands of other foot passengers have been slipping and sliding since the day broke (if the day ever broke), adding new deposits to the crust upon crust of mud, sticking at those points tenaciously to the pavement, and accumulating at compound interest.”

3. A social commentary on the poor and their pitiful state.

“I thought it very touching to see these two women, coarse and shabby and beaten, so united; to see what they could be to one another; to see how they felt for one another, how the heart of each to each was softened by the hard trials of their lives. I think the best side of such people is almost hidden from us. What the poor are to the poor is little known, excepting to themselves and God.”

4. A seething description of the havoc that legal proceedings can have on the life of common man.

“The lawyers have twisted it into such a state of bedevilment that the original merits of the case have long disappeared from the face of the earth. It’s about a will and the trusts under a will — or it was once. It’s about nothing but costs now. We are always appearing, and disappearing, and swearing, and interrogating, and filing, and cross-filing, and arguing, and sealing, and motioning, and referring, and reporting, and revolving about the Lord Chancellor and all his satellites, and equitably waltzing ourselves off to dusty death, about costs. That’s the great question. All the rest, by some extraordinary means, has melted away.”

5. The emphasis on relationships, particularly the love between children and parents.

6. Wicked satire.

7. Excellent characters that seem real enough and relevant, even today.

8. Beautiful descriptive writing.

“I found every breath of air, and every scent, and every flower and leaf and blade of grass and every passing cloud, and everything in nature, more beautiful and wonderful to me than I had ever found it yet. This was my first gain from my illness. How little I had lost, when the wide world was so full of delight for me.”

9. Superlative narrative structure and plot construction

10. Aspects of a murder mystery story that I think Agatha Christie would have approved of.

I spent an entire month reading the 1000 or more pages of Bleak House. It was time very well spent. Could the novel have done with some editing? Perhaps. But then again, it wouldn’t be the same. The ending of Bleak House is satisfying. All the loose ends of the plot are perfectly tied and Dickens, realistically doesn’t provide happiness to all the outcomes. Bleak House is not a bleak novel. It is a beautiful social commentary and the narrator, Esther Summerson is one of the sweetest people to grace the pages of Victorian fiction.